Prototype

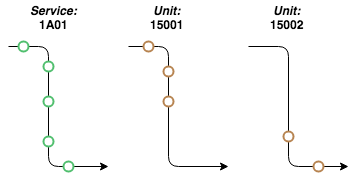

After analyzing the data, we realized that we could divide a service into what we would call segments. A segment would be a small part of consecutive trust reports from one particular service, together with matching GPS reports from another specific rolling stock. For instance, if we analyze the image below, we can see that service 1A01 can be divided up into two different segments.

Based on the idea above, we started experimenting and working out an algorithm that would generate these segments according to a specification that defined how a segment should look in a particular situation. Next, we had to consider a certain amount of edge cases where for example a service was being run by two rolling stock at the same time.

Finally, after we have generated all of the segments we could easily see which if there was a rolling stock that was not supposed to run a service based on the following idea. We first define a segment to be significant if it contains more than x trust reports that have been matched to a GPS report. Then we could iterate over all of the segments and simply see which ones weren’t in the genius allocations. Additionally, since we have the segments, we know exactly where a rolling stock diverted from the diagrams, which makes it easier for a user to see the overall picture of what actually happened.

A basic explanation of how this algorithm worked and performed is provided below.

Simulating Real-time

First of all, we needed to simulate a real-time environment. The simrealtime.py file creates a new thread that simulates that environment by querying the database for trust and GPS reports and calling the appropriate functions when it gets a new report.

The way the simulation works is by storing the next 100 GPS and the next 100 trust reports in two queues in memory. Next, the thread starts off by checking the first value in the GPS and in the trust queue. We compare the time stamps on the reports and store the oldest one in the current variable, take it out of the queue and submit it to be processed. After that, we compare the first value in the GPS queue and the trust queue and choose the oldest one again and store it in the next variable.

Since we want to simulate a real-time environment, the thread sleeps for (next.time - current.time) and then submits the next variable to be processed. Finally, the current variable is set equal to the next variable and we repeat until there are no more GPS and trust reports.

The code also gets the next 100 reports once the GPS or the trust queue gets too small. The reason we only hold a 100 reports in memory is because of scalability. If we want to test the segment generation with more reports, we will eventually not be able to hold all of them in memory.

Report Processing

Until now, we have treated submitting for processing as a high level concept to make the overall concept of real-time easier to understand but it is also an essential part of the simulation.

Once the SimulateRealTime thread is started, it creates a threadpool using the concurrent.futures module with a certain amount of worker threads. These threads are actually responsible for all of the data processing and generating the segments. Every time we submit a report for processing, we check if it is a trust or a GPS report. Depending on the type, we submit it for a different kind of processing. This means that the task gets added to a task queue, which will eventually be executed, as soon as one of the threads in the threadpool is finished processing a previous report.

Segments

What the algorithm currently does is creating segments from all of the reports that are coming in. We define a segment to be a a set of consecutive GPS reports, with their matching trust reports. However the GPS and trust reports in one given segment can only be from 1 rolling stock and service respectively.

These are the main data structures used to store a segment:

Segment:

- cif_uid - String

- gps_car_id - String

- headcode - String

- isPlanned - Bool

- remove - Bool

- matching - Array of Dictionaries

- supposed_to_run: Bool

- GPS - GPS_report

- trust - trust_report

- dist_error - Double

Trust Report:

- id - Int

- headcode - String

- event_time - datetime.datetime

- event_type - String

- origin_departure - datetime.datetime

- origin_location - String

- planned_pass - Bool

- seq - Int

- tiploc - String

- predicted - Bool // If the event was supposed to happen according to the schedule

GPS Report:

- id - Int

- event_type - String

- tiploc - String

- event_time - datetime.datetime

- gps_car_id - String

Constructing Segments

There are 2 main files that are responsible for creating the segments: filter_gps.py and filter_trust.py. Both add, change and delete segments according to a different specification.

Adding GPS Reports to a Segment

- Goes through the segments and finds the most recent one with the same gps_car_id.

- Goes through all of the matching events in those segments and checks if there is potential trust report, that has no matching GPS report.

- It filters those potential trust reports to see if any are within a given tolerance, if there are, it adds the GPS report to that trust report.

- Else if there is no trust report:

- If there is no potential segment, it adds a new one, containing the GPS report.

- Else it adds the GPS report to that segment.

Adding Trust Reports to a Segment

- Goes through the segments and filters out the ones that either have the same headcode as the report or the ones that don’t have a headcode yet.

- In all of those segments, the algorithm looks at the GPS reports, that don’t have a match yet. Then we filter out the segments that contain a potential match for the trust report.

- Another filtering layer, then looks at the unit code of the segment and the headcode of the trust report and checks if that rolling stock was supposed to run the service according to the genius allocations.

- From those filtered segments, it chooses the one with the most matches and the most amount of times that

seqis respected. - If it does not find a segment, it creates a new one, containing the trust report.

- Else it looks through all of the GPS reports that don’t have a matching trust report yet. Then it chooses one, depending on the tolerance and if it respects the

seqfield.

Heuristics

This part attempts to explain the reasoning behind the algorithm described above.

Adding GPS Reports

There are a lot more GPS reports than trust reports. Therefore most of the time, the algorithm will add GPS reports to an existing segment without finding a matching trust report. It does this is by first finding a segment with the same gps_car_id and the most recent GPS report.

For instance if we have two segments, each with a gps_car_id ‘15068’. The first segment represents the time when the rolling stock ran service ‘1A02’ and the second segment represents service ‘1A03’ that it is currently running. We want to add the report to the segment that the rolling stock is currently running and we select it by finding the segment with the most recent GPS report in it.

However we want to create a new segment as soon as that rolling stock starts running a new service. Which is why it also looks for segments with no gps_car_id, and see if it can match the GPS report to the existing trust report(s) in that segment. If it can, it will add the GPS report to that segment. Otherwise, it will look for a matching trust report in the previously found segment and add the report to that.

There are some edge cases where for example it does not find a potential segment. In those cases, the algorithm will often create a new segment. This is for instance found when a new rolling stock starts running.

Adding TRUST Reports

At the same time, we continue to receive trust reports. In the beginning, we do some very similar processing. We go through the segments and filter out the ones with the same headcode as the report. However if we do not find one, that is an indication that this service just started running. In this case, we either look for a segment that does not have a headcode, and look for a matching GPS report. If we find a potential match, we add the trust report to that segment. But if we do not find one, we simply create a new segment.

However what happens most of the time is that we get a set of segments that have the same headcode. This should be a relatively small set so we can look through the matching array and filter out sets that do not have any potential matching GPS reports.

We know that it is more likely for a service to be run by the rolling stock specified by the genius allocation. Hence, we prefer segments with the same gps_car_id as the rolling stock that was supposed to run the service.

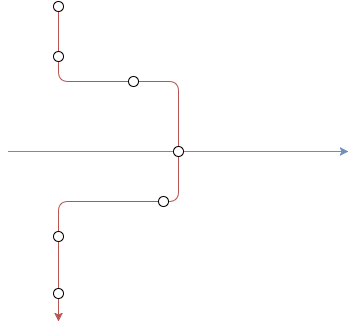

If we still have more than one segment in the set, which is highly unlikely, we need another way of choosing one above the other. The way we decided to do this is by giving a preference to the segment with the most matches. For instance if we look at the figure below, red and blue represent two potentially matching segments. Imagine we are currently processing the overlapping trust report. We would prefer the red segment because it has a higher number of matching reports. Additionally, to be sure we also analyse the amount of times both segments respect the seq value.

All of the above construct the segments with reasonable accuracy, however we still can go over some of the segments and check if we could improve them. This is discussed in the next section.

Interpolating

After we have inserted a trust report, we also perform what we identify as interpolating. It means that we go over a certain amount of segments and try to increase their accuracy.

First, the algorithm goes over a subset of the segments with the same gps_car_id and tries to join them together. For instance if we look at figure 2 below, we can see 3 segments. Each segment is represented by an arrow. The colour of the arrow represents the gps_car_id and the circles represent the trust reports. We can see that in the middle, there is a very short segment with only 1 stop and the two other (outer) segments have multiple stops and have the same gps_car_id. Looking at the diagram, we know that it is very likely that we can combine all three segments into one segment with the same gps_car_id as the first and the last segment. This is exactly what the first step of interpolation does.

The second step then checks if there are any segments, without a headcode yet that might be running the same service as another rolling stock. If it finds such a segment, it adds all of the matching trust report to the appropriate GPS reports.

Finally, after analyzing the data output from the algorithm, we noticed that there were a lot of segments with only trust reports. But these trust reports could have been added to another segment with both GPS reports and trust reports. As you can see below. Imagine the red circles are GPS reports and the blue circles are trust reports. We can clearly see that the trust reports in the right segment can be added into the left segment. However because of the nature of our algorithm, if a new trust report does not find a match in the left segment, it will be added into the right segment.

We carefully considered changing the algorithm to make up for this flaw. But this small flaw was not worth the time that we would spent redesigning and reimplementing a large part of the algorithm. Therefore we decided that we could solve this issue in the interpolation stage. After performing all of the processing, mentioned above, the algorithm also checks if there is a segment with no gps_car_id. If there is, it tries to insert the trust reports in that segment into another segment with the same headcode.

Cleanup Thread

On top of all of this, there is also a cleaner thread. This thread is responsible for going through all of the segments every x amount of time and find segments that have not been updated for a while. After finding those segments, we remove them from the segments in memory. The reason we do this is because the addGPS, addTrust and the interpolate functions loop through all of the segments quite often. However we know that the probability of those functions adding a report to a segment that has not been updated for more than 3 hours is close to 0.

Hence instead keeping having to loop through those ‘useless’ segments, we filter them out. That way we still have access to all of the segments if we need to but we improve the performance of our algorithm slightly.

Overview

All of the above will give you an idea of how the individual bits work, but what the following segment tries to achieve is to explain how all the components are linked together.

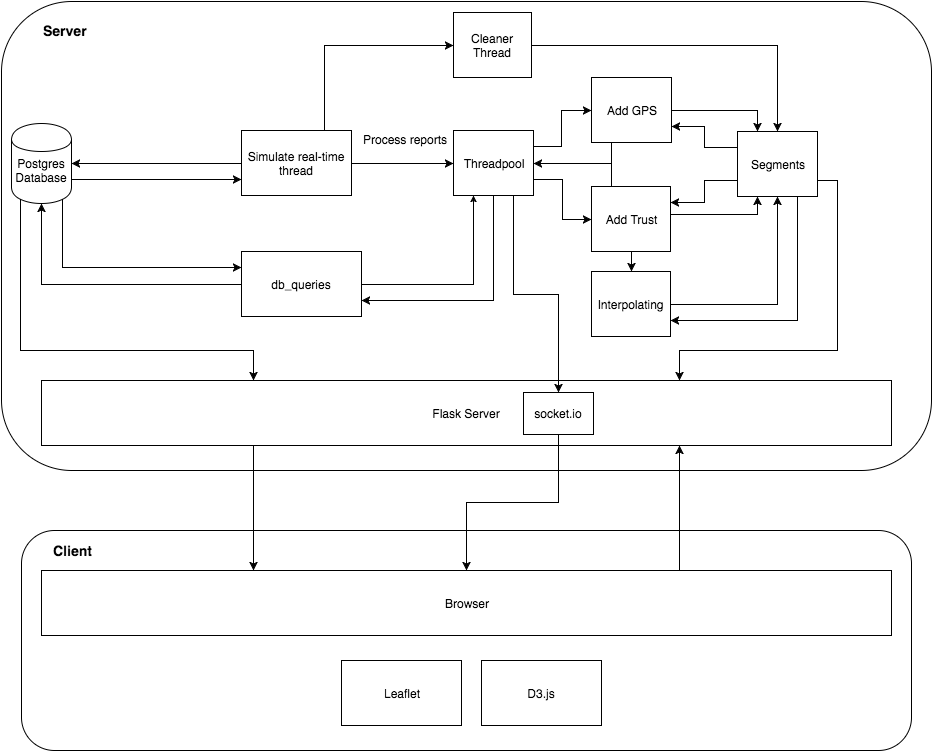

Static Overview

The image below is a static overview of how different components in our system interact. The core of the entire system is the ‘Simulate real-time thread’. It is responsible for simulating a real-time environment where reports come in at a certain point in time. Since all of the data that we have right now is static and stored in our database, the real-time thread continuously requests and fetches new reports from the database.

Whenever the simulate real-time thread simulates a new report coming in, it submits it to the threadpool for processing. Depending the kind of data, one of the threads in the threadpool will either execute the ‘Add GPS’ code or the ‘Add Trust’ code. These two components are the main parts that are responsible for generating the segments. They continuously go over the segments, create new segments and append to the best possible segment.

After one of the threads has added a trust report, it also performs something that we call interpolating. Instead of just manipulating one segment, the thread goes over a large subset of segments and tries to improve their quality by for instance combining or splitting several segments.

On top of doing processing on the segments, the threadpool often requires data from the database. However to abstract away any concurrency issues with querying the database, a separate component, called, db_queries takes care of that. Also, whenever one of the threads changes one of the segments, the socket.io component gets notified to provide a real-time experience in the browser.

Next, the simulate real-time thread is also responsible for instantiating a cleaner thread. This thread was introduced to optimize the algorithm because ‘Add GPS’ and ‘Add Trust’ often loops through a large subset of the segments. But we already know that for some of these segments, there is a tiny probability of a report being added to it. Therefore, the cleaner thread goes over the segments every 10 (simulated) minutes and stores these segments somewhere else.

Finally, we also have a Flask server that deals with the actual communications between the server and the client.

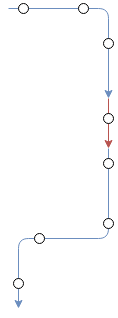

Dynamic Overview

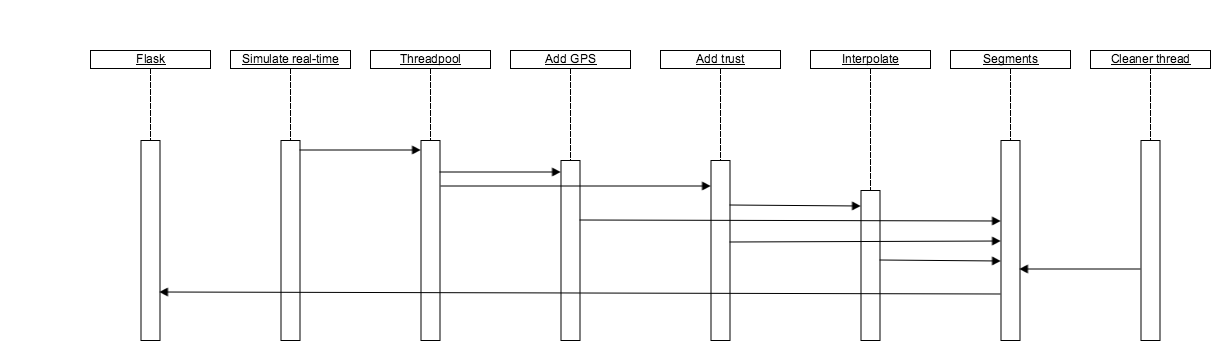

The diagram below is not a real UML sequence diagram, but we use it to show the dynamic behavior of different components on the server. The simulate real-time thread is again at the core of our application and provides the threadpool with reports to be processed. Depending on the type or report, one of the threads then executes the ‘Add GPS’ or the ‘Add trust’ code. Both of these components then update the segments. Each time, after a thread has executed the ‘Add trust’ code, it also performs interpolation on a subset of the segments, which then, in turn, updates the segments again.

Every 10 minutes, the cleaner thread also goes over the segments and removes any that it considers to be ‘dead’. Finally, whenever flask serves the application, it fetches all of the segments (including the dead ones).

Performance

The algorithm constructed the segments according to our specifications to a reasonable extent. Unfortunately due to the nature of the problem, there is no way to test the outputs programmatically but after carefully analyzing the data ourself, we can conclude that the outputs could have been used, together with some human assistance to identify all of the rolling stocks that divert from the genius allocations. There were however still various problems with this approach.

Problems

- There were some flaws in the initial design of the algorithm, one of which has already been outlined above in the interpolating section. Most of these could be solved by adding processing to the interpolating stage, but that brings us to the second point.

- Adding GPS and Trust reports is a relatively fast process and so was interpolating initially. However due to the processing that was added later on to the interpolating stage, it has become a very CPU intensive process.

- Due to the many threads in the algorithm, it has exploded in complexity. Even though the general idea is still easy to understand, the complexity introduced by concurrency makes it hard to start contributing to the algorithm.

Due to all of these problems, we decided that the segments were not the right way to go. Instead of having to oblige to a set of specifications that the segments introduced, we wanted to implement a simpler algorithm.